By Amanda Gobeli, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Associate

By all accounts, 2016 appears to be another “boom year” for quail, with enthusiasts across Texas and neighboring states celebrating the return of the birds, enjoying favorable hunting prospects, and even declaring the quail decline to be over. Anecdotes of brood sightings and more coveys are encouraging, but what do the data say about how quail numbers this year compare to last year’s boom? More importantly, is the drought truly over and can we safely attribute the quail decline to a simple lack of rain?

|

| Texas Parks and Wildlife Department 2016 roadside count data for the Rolling Plains illustrates the population spike observed this year and last. |

The Texas Quail Index consists of 5 demonstrations for evaluating

factors that affect quail trends in Texas: (1) spring call counts estimate breeding capital, (2) roadside

counts measure quail abundance post breeding season, (3) dummy

nests indicate how predators are impacting reproductive efforts, (4) game

cameras are used to see what types of predators are present on a property, and (5) habitat

evaluations reflect the abundance and distribution of quail resources in the

environment. Each represents an important variable in the “quail equation.”

|

| Volunteers prepare to conduct a TQI demonstration. Photo courtesy of Bosque County. |

|

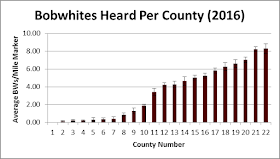

| A graph of spring call count results for the TQI, showing the average number of roosters heard per stop in each county. Participants conduct counts at 8 "male markers" 3 times per year. |

Scaled (blue) quail exhibited overall lower call count averages

in the TQI but have seen a significant increase. The 2014 value for

average roosters heard per stop was 0.30 in 2014, a slightly higher 0.56 in

2015, and 2.63 in 2016. The top ecoregions for scaled quail this year were the

High Plains (average of 3.8) and the Edwards Plateau (average of 2.3).

|

| There was no shortage of rain in Texas in early spring of 2016. Some parts of the state arguably could have done with a bit less. |

Perhaps the most important factor in this year’s call count

decrease is that some regions experienced too

much rain. Nowhere was this more evident than in the Gulf Prairies and

Marshes in the eastern part of the state. Bobwhite populations in this region spiked

in 2015, but took

a nosedive this year. TQI cooperators from the area reported flooding which

made data collection difficult to impossible or rendered call counts abnormally

low. Weather can also affect call counts in less dramatic ways, as rain and

wind can suppress calls or make them hard to hear (Rollins et al. 2005). In areas not subjected to

flooding, where habitat quality benefited from the increased moisture, call

counts typically remained high.

For more information, check out these resources:

Literature Cited

- Gill, J. 2016. Quail populations on the rebound. Standard-Times. <http://www.gosanangelo.com/sports/outdoors/hunting/quail-populations-on-the-rebound-38135703-3e2f-4558-e053-0100007f1ecf-389512891.html>. Accessed 11 Nov 2016.

- Hernández, F., and F. S. Guthery. 2012. Beef, brush, and bobwhites: quail management in cattle country. 1st ed., Texas A&M University Press ed. Perspectives on south Texas, Texas A&M University Press, College Station.

- Hershberger, A. 2016. Opening weekend proves to be worth the wait. JournalStar.com. <http://journalstar.com/sports/local/outdoors/opening-weekend-proves-to-be-worth-the-wait/article_10502d5a-0276-5e3d-b75d-0275f97b0574.html>. Accessed 11 Nov 2016.

- NOAA, and NWS. n.d. Monthly Observed Precipitation for the State of Texas. <http://water.weather.gov>. Accessed 11 Nov 2016.

- Rollins, D., J. Brooks, N. Wilkins, D. Ransom, and others. 2005. Counting quail. Texas FARMER Collection. <http://oaktrust.library.tamu.edu/handle/1969.1/87340>. Accessed 11 Nov 2016.

- Rollins, D., and B. Ruzicka. 2015. Texas Quail Index: Team Handbook. Texas A & M University Press. <http://wildlife.tamu.edu/files/2013/12/TQI_handbook.pdf>. Accessed 11 Nov 2016.

- Tompkins, S. 2016. Texas’ quail population drought is over. Houston Chronicle. <http://www.houstonchronicle.com/sports/outdoors/article/Texas-quail-population-drought-is-over-10415971.php>. Accessed 11 Nov 2016.

- TPWD: Bobwhite and Scaled Quail in the Rolling Plains. 2016. <http://tpwd.texas.gov/huntwild/hunt/planning/quail_forecast/forecast/rolling_plains/>. Accessed 11 Nov 2016.